Swift has a pretty decent C-interoperability story. But C has many features! Today, I'll tell you a story involving a few not-so-well supported C features and Swift.

It all started when I decided to re-write Pathos with Windows support. One of the library's

offering is reading the literal target of a symbolic link: if b is a link to a, then

Path("b").readSymlink() should return a another path that's equivalent to Path("a").

The Windows API that returns this information is DeviceIoControl:

BOOL DeviceIoControl(

HANDLE hDevice,

DWORD dwIoControlCode,

LPVOID lpInBuffer,

DWORD nInBufferSize,

LPVOID lpOutBuffer,

DWORD nOutBufferSize,

LPDWORD lpBytesReturned,

LPOVERLAPPED lpOverlapped

);

Notice anything weird? Hint: LPVOID is void * in standard C.

This function is, for the lack of better words, polymorphic: depending on your input, it can intake

and output different types. As a caller, it is your responsibility to look up what type is needed

and cast them to and from those void *s. The size of the data structure is returned as well. We'll

have a lot to talk about that later.

Perhaps, surprisingly, this is not too hard to deal with in Swift. In my last article, I detailed how we can use an Swift API to work with C buffers:

/// get the file `handle`...

/// now call `DeviceIoControl`

var data = ContiguousArray<CChar>(

unsafeUninitializedCapacity: kMax

) { buffer, count in

var size: DWORD = 0

DeviceIoControl(

handle,

FSCTL_GET_REPARSE_POINT,

nil,

0,

buffer.baseAddress,

DWORD(buffer.count),

&size,

nil

)

count = Int(size)

}

So this fills the array of CChars with the necessary bytes for out result. I named the variable

data because it is exactly the same concept as Foundation's Data, as most Swift programmers

know.

As promised, we'll cast this data to the actual type so that we can retrieve information from its bytes. Side note: casting in this context is a documented usage, So it really is more awkward rather than bad. And there's a safe way to do it:

withUnsafePointer(to: data) {

$0.withMemoryRebound(

to: [ReparseDataBuffer].self,

capacity: 1

) { buffer in

// first element in `buffer` is

/// a `ReparseDataBuffer`! Yay

}

}

It's very important to note that ReparseDataBuffer is a struct with fixed, predictable layout,

that the API DeviceIoControl promises to return. In practice, this means it is defined in C. Swift

does not currently guarantee struct layout. So unless you really know what you are doing and don't

care about forward compatibility, you should not do this with Swift structs.

So far this story has been boring for avid Swift programmers. Fear not, things will get spicy now.

Let's talk about this ReparseDataBuffer. It's an imported C type with a few notable features.

typedef struct {

unsigned long ReparseTag;

unsigned short ReparseDataLength;

unsigned short Reserved;

union {

struct {

unsigned short SubstituteNameOffset;

unsigned short SubstituteNameLength;

unsigned short PrintNameOffset;

unsigned short PrintNameLength;

unsigned long Flags;

wchar_t PathBuffer[1];

} SymbolicLinkReparseBuffer;

struct {

unsigned short SubstituteNameOffset;

unsigned short SubstituteNameLength;

unsigned short PrintNameOffset;

unsigned short PrintNameLength;

wchar_t PathBuffer[1];

} MountPointReparseBuffer;

struct {

unsigned char DataBuffer[1];

} GenericReparseBuffer;

};

} ReparseDataBuffer;

Feature #1: it has a union member.

A union in C is an area in memory that could be any of the types specified in the union:

// X.a is a `char` and X.b is a `uint64_t`.

// And they occupy the same memory because

// only 1 of them exists at a time.

typedef union {

char a;

uint64_t b;

} X;

Swift does not own a direct analog for this. So if we import this ReparseDataBuffer definition,

there wouldn't be a good way to access the data inside the union.

As I pointed out in the comment, members of a union occupy the same space in memory. The largest member defines the size of that space, so everyone can fit inside of it. Each union member interprets the same bytes according to their own definition. Given this knowledge, we can derive a solution that works around Swift's limitations: break up the union (sorry, this whole paragraph reads super suggestive of the real world union. It's probably why this word is picked for this data structure in the first place. But I do not intend to say anything about the real world here)!

typedef struct {

unsigned long reparseTag;

unsigned short reparseDataLength;

unsigned short reserved;

unsigned short substituteNameOffset;

unsigned short substituteNameLength;

unsigned short printNameOffset;

unsigned short printNameLength;

unsigned long flags;

wchar_t pathBuffer[1];

} SymbolicLinkReparseBuffer;

typedef struct {

unsigned long reparseTag;

unsigned short reparseDataLength;

unsigned short reserved;

unsigned short substituteNameOffset;

unsigned short substituteNameLength;

unsigned short printNameOffset;

unsigned short printNameLength;

wchar_t pathBuffer[1];

} MountPointReparseBuffer;

// we don't care about the 3rd union

// member in this use case

Conveniently for us, the union member in ReparseDataBuffer is at the end. So we don't need to

worry about padding the unused space for smaller alternatives. Back in Swift, instead of dealing

with ReparseDataBuffer directly, we can work with SymbolicLinkReparseBuffer or

MountPointReparseBuffer, depending on our expectation of which union member to read.

Yeah, this is a good time to mention that, Pathos has to include copies of these definition in a

separate C module. Not only because we need to "break up the union", the original definition is also

only accessible after importing some headers in the NT kernel. So the standard import WinSDK won't

suffice.

Moving on to notable feature #2. The last member of both SymbolicLinkReparseBuffer and

MountPointReparseBuffer pathBuffer is a 1-character long array...why?

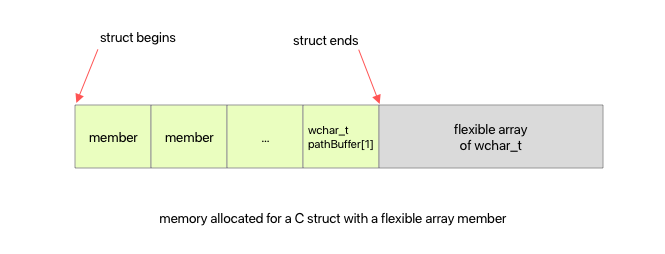

In C, this is a flexible array member. Such member must always appear at the end of a struct.

The word "flexible" in this context refers to the amount of memory allocated for this type of

structs : it can vary according to the length of the array as needed. The member such as

pathBuffer is here to provide access to the beginning of the buffer.

To Swift, pathBuffer looks like a single UInt16. The language obviously don't have a good idea

of this C feature. So how to we get the rest of the data from this array?

Once again, we have to lean on our understanding of memory layout in C structs.

As is common in APIs for flexible array members, the length of the array trailing the struct is

provide to us. Let's call it flexibleLength.

We already have the memory for these structs in bytes (remember data?). And we can get the size

for the fixed potion of the structs with

let fixedStructSize = MemoryLayout<

SymbolicLinkReparseBuffer

>.stride

Putting it all together, we can get the full content of the array by

- chopping off the content for struct itself,

- casting the rest of the raw buffer to the expected element type, and

- include the last member in this struct as the first element in the array

// Include the first element, which is at

// the end of the fixed struct potion.

let arrayStart = fixedStructSize - 1

// Cast the data buffer so it's composed

// of `wchar_t` aka `UInt16`s.

let array = withUnsafePointer(to: data) {

$0.withMemoryRebound(

to: [UInt16].self,

capacity: data.count / 2

) { sixteenBitData in

// chop off the non-array potion

sixteenBitData.pointee[

arrayStart ..< (arrayStart + flexibleLength)

]

}

}

// now, go nuts on the array! You earned it!

Considerations such as error handling are intentionally left out in this article. You can checkout

the source code of Pathos (on the next branch) for the full glory.

Anyways, the flexible array member turns out to be the literal target of the symbolic link. So here is the end of our story. I'm interested to hear about alternative approaches for dealing with union members and flexible array members in Swift. Let me know on Twitter, or Twitch when I'm streaming!